by Francesca Rheannon

Part One: The Jews

“McDO, that’s a Jewish business,” my host Michel said contemptuously. I was staying with him and his wife, the lovely Marie-Jo in Apt, an ancient Gallic-Roman city in the south of France. The year was 2002 and I was in Provence to gather research on a book.

The couple had generously opened their home to me, someone they barely knew, and we had quickly become fast friends. Michel was a private chef; his wife was a nurse who was taking leave from her job to care for her elderly invalid mother who lived next door.

Michel had not always been a chef. He was a man of many sides and a checkered past. He didn’t fit easily into any categories. For one, he had spent close to a decade in prison during his youth. The details were never really forthcoming, but it had something to do with underworld gangs in Marseilles. He would have looked the part, too, with his street tough’s body, all barreled and bandy-legged, were it not for his warmth and ebullient nature.

It wasn’t the first time I had heard him place the adjective “Jewish” next to a subject of opprobrium. Over the past two days, he had excoriated the “Juifs” in Israel and noted that someone who had charged him too much money for a service was a Jew. Now this.

Michel is a man of contradictions; he can cleave tenaciously to odious ideas — ideas that go utterly counter to his generosity of spirit. The moment had come to challenge them.

“How is that?” I asked. “Monsieur Kroc, he’s a Jew,” he answered, as if informing me of the obvious.

Was this true? I wondered briefly to myself. Then I remembered with a Homer Simpson dope slap that it didn’t matter. “You know, most big corporations are headed by Christians, but nobody accuses them of being Christian businesses’,” I said mildly, and walked out of the room, too rattled to pursue the subject. But I resolved to pick up the issue at a later time, soon.

That evening, as we basked in post-dinner bonhomie, mellowed by a good rouge from a local vineyard, I thought the time might be ripe. I took up the question of Israel, since I knew it was one on which Michel and I had some agreement.

“You know, Israel’ and the Jews’ is notnecessarily the same thing,” I began. “There are many Jews, both inside and outside of Israel, who are against Israeli policy and the occupation. It’s not a simple issue, and there’s right and wrong, and terrorism, on both sides. Israel has a right to exist — and its creation was a response to the extermination of the Jews in Europe.”

Michel pulled on his Gaulois thoughtfully for a moment. “You’re right,” he said. We’d made it to first base, but he wasn’t off the hook.

“Why does there seem to be so much anti-Semitism in Europe?” I pressed on. I waited through another silence. Michel sighed.

“I think it is because we feel guilty,” he responded quietly. “We feel guilty for the Holocaust. There were many here in France who did nothing, who let the Jews be taken away to the gas chambers. The Vichy government gave the Nazis a cadeau, a gift: the list of all the Jews registered in France. And we all share in that shame.”

Jews In Provence: Early Times

The history of the Jews in France is complex. On the one hand, expulsions beginning in the twelfth century, pogroms, and show trials like the Dreyfuss Affair attest to a long history of persecution that ranged from the horrific to the merely shameful. On the other hand, the French Revolution established the equality of Jews as citizens under French law, abolishing forever their separation from the rest of society (except for the years 1940 —1945, under the German Occupation and Vichy). The new republic was the first European government to do so.

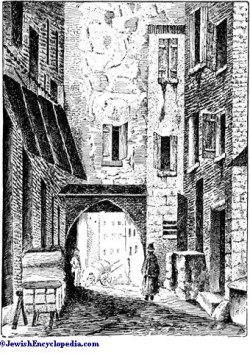

In Provence, the story is even more contradictory, with welcome (or at least tolerance) and rejection playing out over different areas and times. Jews first came to Provence, then part of the Roman province of Gaul, sometime in the first century C.E. Two cataclysmic events propelled them from the Holy Land: the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem and the fall of Masada.

The region again became a refuge when English Jews fled to Provence in the thirteenth century. And over the next hundred years, conditions deteriorated for France’s Jews, culminating in their expulsion in 1394. At that time, Provence was not French but part of the larger region where the “Langue d’Oc” was spoken. The Papacy took over a portion of the region in 1305 when the Pope moved to Avignon.

Jews settled in various cities of the region: first of all in Carpentras, where the Pope sent them, then spreading south and east to Salon de Provence (where Nostradamus, a converted Jew, lived) and the towns bordering the Calavon River: Cavaillon, L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, and Apt (where Michel lives.)

They practiced a wide variety of trades, particularly wine growing along the banks of the Rhone. They were farmers and diplomats, scribes and translators, as well as traders and moneylenders. But the Black Death decimated their communities, as it did all Provence. The general social crisis brought on by the plague led to attacks on many Jewish communities, especially those in Haute Provence, including Manosque, Digne, and Forcalquier.

Jews In Provence: The Middle Ages

In the fourteenth century, Jews from northern Spain (Catalonia) found refuge in Arles and Tarascon, but in the fifteenth they were brutally expelled from those cities. In 1348, Pope Clement VI invited them to settle around his palace in Avignon and in the Comtat Venaissin, that area of Provence that was under the papal jurisdiction and today makes up part of the Vaucluse.

They had the right to practice their religion and live in peace, but they paid for that right in the coin of heavy taxes to the Pope’s treasury. And they were marked: required to wear a badge, or “rouelle”, that identified them as Jews.

Jewish immigrants to southern France brought a wealth of literature and knowledge with them, stemming from the lively cross-fertilization of Hebrew, Christian and Muslim thinking and discovery. A tradition of Jewish/Arab learning existed in Provence at least since the twelfth century and possibly before that.

More of that in the next installment. (Can’t wait? Read the entire post here.)

One thought on “Memories of Xenophobia: What I Learned About Christians, Jews & Muslims in Provence”

Comments are closed.