Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

WV host Francesca Rheannon talks with former health insurance industry executive and whistleblower Wendell Potter about how the attacks on Medicare For All are being fueled by health insurance cash to Democrats.

WV host Francesca Rheannon talks with former health insurance industry executive and whistleblower Wendell Potter about how the attacks on Medicare For All are being fueled by health insurance cash to Democrats.

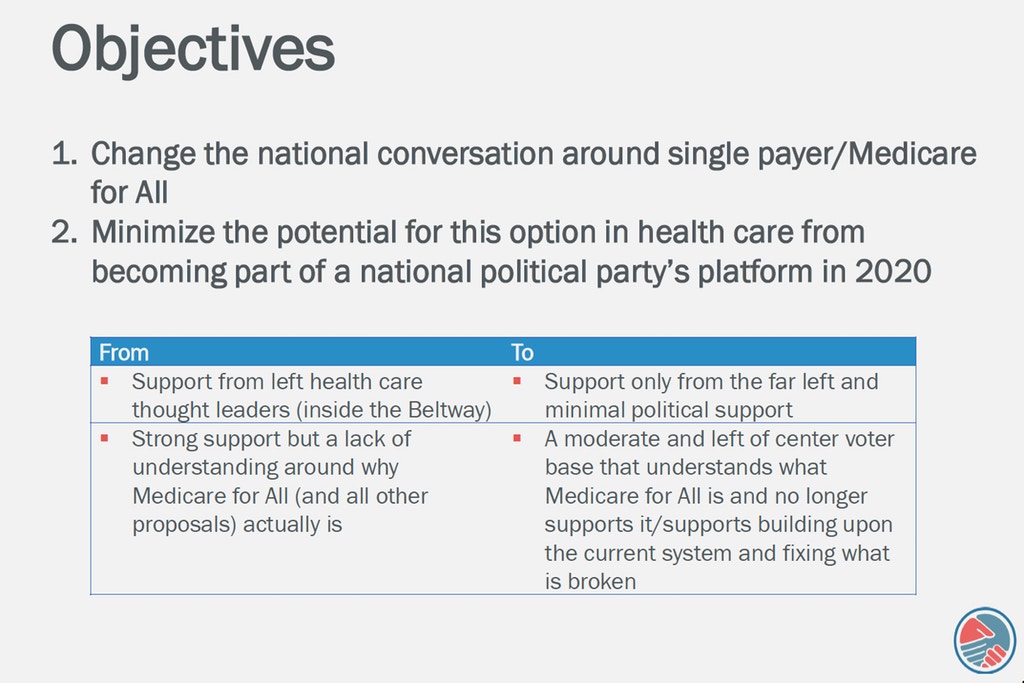

The health insurance industry is mounting a full court press against Medicare For All. Wendell Potter says one big way they’re doing that is by spreading their talking points to politicians on both sides of the aisle who have taken big donations from them.

Potter had an inside seat to the process when he was a health insurance executive for Cigna. He blew the whistle on the industry with his books, Deadly Spin and Nation On the Take, both of which he’s talked about on Writer’s Voice.

Potter went on to found the website Tarbell.org, which does investigative journalism on the healthcare industry. (We spoke with him about Tarbell’s report on why drug prices are so high here.) This week he wrote a post on Tarbell about the new Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC)Â Chair, Cheryl Bustos, who was a top recipient of health insurance industry campaign contributions.

Francesca spoke with Potter about Bustos and also about health insurance talking points against Medicare For All, which Potter rebutted, one by one.

Other Posts by Wendell Potter on Democrats on the take:

http://wendellpotter.com/2019/02/how-to-spot-the-health-insurance-industrys-favorite-democrats/

http://wendellpotter.com/2019/03/potter-sen-donnelly-kept-health-care-reform-efforts-at-bay-his-whole-tenure-in-congress/

Transcript of Wendell Potter’s Interview with Francesca

Francesca: Wendell Potter, thanks so much for talking with us here. You wrote a post about an article published by The Hill, a story that they published earlier in March, “DCCC chief says Medicare for all price tag a little scary.’” This new chief of the DCCC is Representative Sherry Busto of Illinois. Tell us about her in the context of this post.

Wendell Potter: Well, I was not necessarily surprised to see that headline because earlier, last year, just before the New York primary, in which Alexandria Ocasio Cortez was taking on Joe Crowley in a district in New York, I was looking to see how much money Crowley had taken from healthcare special interests. And I was looking to see in particular which members of Congress had taken the most from the five largest health insurance companies and their political action committees. And lo and behold, Crowley was right up there in the top five.

But heading the list was Cheri Bustos. So I was a not a bit surprised to see that story. She has a history also of working for a big hospital system, a big integrated health care system in the Midwest. So I thought it was important to help people understand just where she’s coming from and the fact that she has become someone who is really quite expert at taking sizable checks from big special interests, and certainly those from health care.

FR: You write that she was vice president of corporate communications for a big hospital system. What skin in the game do the hospital systems have, when we’re talking about Medicare for all?

WP: They’re very much involved. In fact, there’s this front group that was formed last year by health insurance companies, pharmaceutical companies, and big hospital chains through their trade associations, the American Hospital Association and the Federation of American Hospitals, which is the for-profit hospital organization and they’re pooling their money–all these parts of healthcare–to finance collectively this campaign against Medicare for All.

And the hospitals are against it because they’ve got a good thing going. One of the things I often tell people is that it’s not really accurate to think that health insurance companies are really all that much in the game to control healthcare costs. They’re not. They can’t, for one reason or another, nor do they have a reason to do it or an interest in doing it, because the more healthcare costs go up, the more money they get or are able to demand from us in terms of premiums.

Hospitals are in on the game, in that, because health insurance companies cannot really control health care costs, they can pretty much have their way with them. So they like the system as it is. They get more money from private insurers than they do from the current Medicare program or from the Medicaid program, and it’s because of the weakness and the smallness of individual private insurance companies.

FR: And yet they’re pretty big nonetheless, a huge part of our economy. You talk about Bustos getting the most contributions from the PACs of all five of the biggest for profit health insurers: Aetna, Anthem, Cigna, Humana and UnitedHealth Group. You say she’s being supplied with talking points by the health insurance industry. What are her talking points?

WP: Well, here’s how it works. If you are on the take from big industry, you’re more willing, and your staff is more willing, to see a lobbyist from those who are writing those big checks. And some of the talking points here are that this country can’t afford Medicare For All, that it would cost too much money and that so many Americans get their coverage through their workplace; that we need to be mindful of that as we’re looking at Medicare For All.

Those are talking points directly from the insurance industry, and this partnership that I mentioned, to scare people, to make them think that this is really not something that we should strive for, that there are these reasons why we shouldn’t even give it any consideration. It is true, most Americans who are not enrolled in Medicare or Medicaid or some other public program do get their coverage through private insurers.

That’s the way it’s been for in this country for many, many decades. But it doesn’t mean it always has to be that way. And the reality also is that many people who are enrolled, in fact an increasing, probably a majority, of people enrolled in private insurance plans, in particular, those through their workplace, are finding that their coverage is increasingly less valuable even though they’re paying more for it–they and their employers–every single year. So I know that in reality a lot of people are very dissatisfied with what they’re getting for the high premiums they are paying and they’re having to pay more and more out of their own pockets these days for coverage, even if they have insurance. But that’s one of those talking points. It is to try to make policymakers and the public believe that for some reason our employer based system is sacred, that we can’t touch it.

FR: Yes. I remember the last time I got health insurance through an employer, they instituted a new program called Value Plus and I used to joke that it was more like Value Minus, because I was paying a lot more for a lot less.

WP: Right. In fact, my last CEO in the health insurance business, at Cigna, someone asked him what kept him up at night and he said it is the worry that employers and individuals will wake up and question the value proposition of health insurers, which is a wonky, jargony term that’s often used in business, certainly in health insurance, and I think employers and individuals are waking up to question–and rightfully so–the value proposition; what value do they actually bring to this country? And it’s questionable.

One of the things I used to have to do for a living was was to try to make people believe that we had a reason to exist, but increasingly employers in particular are questioning the reason why we have this middleman in the equation in the first place.

FR: Let’s go to some of the other talking points. Bustos was saying a $33 trillion price tag for Medicare For All is just too much. You counter that.

WP: Well, that actually is only part of the number that this think tank–actually a conservative think tank–came up with. So she’s quoting that. But even that think tank said that is at least $2 trillion less over 10 years than what it would be if we continue with the current system. So in other words, even that—yes, that’s a big number—but it’s over 10 years, first of all. And what she did not tell or say was that that would represent less money than the country would spend on healthcare if we go to Medicare For All than if we don’t.

The reality is that this year, we’ll spend three and a half trillion dollars on healthcare as a country. So if you multiply that by 10, you’ve already gotten over $30 trillion, $35 trillion. And that is just based on the assumption that there will be no medical inflation, which of course that’s something you have to factor in. So if we stick with what we’ve got, we will be spending a heck of a lot more than $33 trillion over the course of the next 10 years. So it’s very disingenuous for her to use that number out of context that she did.

FR: Now, the third talking point is “think of all the jobs that are going to be lost for people who are processing all those claims — or denying all those claims.

WP: Right. And I think it’s a talking point to obscure the reality that the work that they do makes it, in many cases, impossible for the rest of us, the many millions of us, to get the care that we need. A lot of these folks, as you pointed out, are employed to try to avoid their companies paying claims. Because we have a multi-payer system, which is unique in the world, insurance companies not only have armies of employees who are in the business of determining whether or not someone should get coverage for whatever it is a doctor recommends, but you also, on the provider side, have to have armies of people who do nothing more than deal with insurance company bureaucrats day in and day out. So you’ve got these tens, if not hundreds of thousands of people who are employed in our healthcare system who do not do anything to make us better or to help us with our health. In fact, in many cases it keeps us from getting the care that we need.

The other point I would make –two points, actually: insurance companies have employed literally tens of thousands of nurses who are not providing care, but they are working for these big insurance companies, in many cases standing in the way of the care that we need, And medical directors, doctors, as well. So in my view, those folks have been trained as caregivers; they should be back at the bedside or providing care in offices, rather than making it more difficult for us to get care.

The other thing is that most of these big insurance companies have diversified over the years. They would not go out of business if we move tomorrow to a Medicare For All plan. They’ve got other lines of businesses that are really quite profitable and are growing. So it’s a fallacy to say that these companies will go out of business. Some people would need to be retrained. Some of them have great training like doctors and nurses and could go straight away to work at a better place, in my opinion.

FR: That’s a great point. You don’t talk about the following in your piece, but another talking point I’ve heard coming more from, let’s say, the center left: many people in the Democratic Party are saying they are for Medicare for All (although they’re beginning to hedge on some of that) and some of the 2020 candidates are saying, “well, we just want universal coverage and we can do it with the kinds of plans that, let’s say, Switzerland has or Germany or Holland, where there are private nonprofit insurance companies that the government pays and bargains with.” So what is the best way to do health care for all?

WP: I’ve heard that too. Obviously my response is, why in the world would you not want to do the best job? Why would you want to emulate another country that, yes, they have achieved universal coverage, but they’re kind of runners up with us in terms of how much they spend on healthcare. We spend almost $10,000 per person per year on health care, which is twice the average of other developed countries and we have worst outcomes than most of those countries, so we have very little to show for all that we’re spending. But Switzerland comes in second in terms of the amount of money that the country spends on healthcare. Germany’s not too far behind.

The thing that is distinctive about those countries is that the insurance companies or sickness funds, as they may be called in those countries, are heavily regulated, price regulated. They’re all nonprofit entities. And we’ve moved far away from that kind of structure many decades ago. So insurance companies would be just as resistant to a proposal like that that would force them into nonprofit status as Medicare for All.

Why do we want to do a half measure? Why do we want to postpone what is inevitable, which is moving to a single payer healthcare system? And it is the one system of those that are proposed that not only would get us to universal coverage but would save us the most money.

In fact, when the Affordable Care Act was being debated, policy makers knew that we needed to try to do something about healthcare costs, while also trying to achieve the goal of universal coverage. Policy makers decided during the Obama administration to go first for universal coverage and deal with healthcare costs later. We see where we wound up. We wound up with a bill that does a great deal of good in terms of bringing a lot of us into coverage, but there’s still about 30 million of us who are uninsured.

And the other problem is that a fast growing percentage of us are under-insured, because of the way that law is structured and the way that the insurance industry has been going, which is to move every last one of us into a high deductible plan. And increasingly, those of us who are low and moderate income have trouble meeting our deductible. So we go without care. That’s the definition of underinsurance. So why do we want to do second best or third best? Why don’t we just do something that really gets us to where we need to be rather than just continuing to tinker with the system that has failed us for many years?

FR: And the other thing that I’ve heard coming out with some of the candidates—and I’m thinking of Jay Inslee—are proposals to decrease the Medicare eligibility age to 55 or 50. In other words, an incremental approach. And the other one is to provide a public option that businesses and people could buy into. In other words, people could buy into Medicare. What are your thoughts on those proposals?

WP: Well, you know, it would be better than not doing anything, I guess. But again, why do you want to settle for something that is not as good as you can try to get?

FR: Well, the reason is politics.

WP: The reason is politics. But like I said, you can expect as much resistance to that as you would to going boldly. In fact, an American historian was interviewed on TV not too long ago saying, if you look at American history or history broadly, you’ll see that sometimes it’s easier to achieve sweeping change by bold views than by incremental change. Incremental change can be incredibly tough to pull off. Sometimes bold measures are more successful.

But back to that specific proposal, it would add complications to the system; instead of simplifying the system, it just adds greater complexity. And you would keep the insurance industry in place for however long–maybe indefinitely. It is our multi payer system and the complexity of our system that is at the heart of our problem with costs being out of control.

And I just see that as a real cop out to being able to get to where we need to be. It does nothing to curb the practices of the insurance industry that are putting more and more of us into the ranks of the underinsured, for example, which is limiting the choices of doctors and hospitals we have in these so called limited or narrow networks that are in vogue among health insurance companies. Now, in fact, almost all of them have limitations to the doctors and hospitals you can see. They’re forcing you to pay more and more for prescription medications by putting more and more drugs in tiers that cost you more or require that you pay more out of your own pocket. They’re making you pay more out of your own pocket broadly through high deductibles. Why do we want to keep a system in place that makes us pay more for care out of our own pockets, even if we have insurance, and to pay more and more every year in premiums? That doesn’t make sense to me. And I can’t imagine why policy makers would propose that we keep a system like that in place just because it might be easier. It makes no sense to me.

FR: This is affecting cancer drugs too, isn’t it?

WP: Yes. In fact, I draw your attention to a piece that is on Tarbell now written by a leading oncologist from MD Anderson in Houston about the cost of oncology drugs. And it’s just extraordinary what has happened to the price of pharmaceuticals broadly, but in particular for cancer drugs. And insurance companies are just largely on the sidelines because they are not large enough. Not any of them, even the biggest, have enough clout to really do anything to control drug prices. All they are able to do is shift us, require that we take one drug as opposed to another that our doctor might have recommended, or again, shift those medications into tiers that make us pay more. So they’re not controlling costs, they’re shifting more of the cost to us. And in many cases, as this doctor who wrote that piece pointed out to me, he has seen patients die for economic reasons. They just simply can’t figure out the resources to get the medications or the treatments that they need.

FR: Well, Wendell Potter, this has just been really great to have you talking with us here. Thanks so much. And we’ll keep on staying tuned to Tarbell, your investigative reporting site on the healthcare industry.

WP: Thank you very much, Francesca. Yes. Please check out Tarbell.org.